For developers and engineering, procurement and construction (EPC) providers in the United States, decision-making logic is undergoing a structural shift. While cost and delivery timelines once dominated procurement considerations, greater emphasis is now being placed on supply-chain controllability and compliance. The market is sending a clear signal: whether a supply chain is compliant and controllable has become the first gatekeeper to accessing the US solar market.

The drivers behind the shift in procurement priorities cannot be explained by any single policy measure. Reciprocal tariffs, the final rulings of the antidumping (AD) and countervailing duty (CVD) investigations into four Southeast Asian countries (Vietnam, Cambodia, Malaysia, and Thailand), and a new round of investigations targeting Laos, India, and Indonesia unfolded in close succession throughout 2025, injecting a high degree of uncertainty into shipment schedules.

This confluence of policies has created a lasting bottleneck. Customs clearance timelines have lengthened, documentation reviews have become repetitive, and in some cases, cargo release decisions have come down to the last minute. Even when orders remain intact, actual shipment volumes at many companies continue to contract. The decline has been most pronounced among manufacturers without module production lines in the United States. Companies with domestic capacity have seen relatively more stable shipments, although none has experienced a material surge in volumes.

UFLPA compliance

Beyond trade policy measures, the long-term compliance pressure stemming from the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA) cannot be overlooked. Since 2022, solar cells and modules have been included in US Customs’ high-priority inspection category for “electronics,” with the cumulative number of detained shipments reaching into the thousands. The primary source of pressure has not been outright denial of entry but prolonged periods of “pending determination,” which often impose greater strain on project schedules and cash flow than outright re-export.

This enforcement focus has gradually expanded from Malaysia and Vietnam to Thailand, India, and Mexico, eroding the effectiveness of simple country-of-origin switching as a viable risk-avoidance strategy.

Against this policy and compliance backdrop, the importance of a US-based supply chain has risen significantly. Companies with domestic module manufacturing capacity, such as First Solar, have demonstrated substantially greater shipment stability than competitors without US production footprints.

At the same time, domestic manufacturing is suffering its own risks. The sourcing of modules, cells, and even upstream polysilicon and wafers remains subject to traceability and compliance scrutiny, with supply-chain risk gradually shifting from the “border” to the “upstream” segments.

Domestic manufacturing

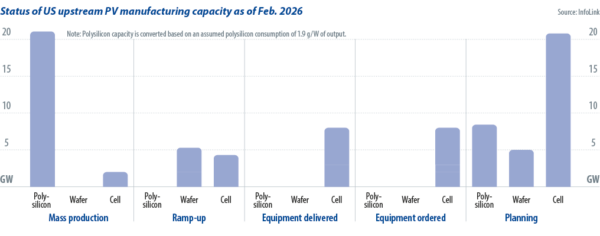

Despite strong policy incentives and robust market demand, the rollout of domestic capacity remains constrained by multiple factors. As of the end of 2025, InfoLink data show that nameplate US module capacity had reached 73 GW, which in theory is sufficient to cover domestic demand. In practice, the ability to sustain stable output so far remains well below stated headline capacity figures for many manufacturers.

Progress across the supply chain has been highly uneven. At the polysilicon stage, the two producers active in the United States, Hemlock Semiconductor and Wacker Chemie – have a combined capacity of roughly 40,000 MT, equivalent to around 21 GW. This level has remained unchanged for several years, though Hemlock says it has recently expanded capacity to meet new demand from the wafer factory opened in 2025 by its parent company Corning, without specifying by how much. REC Silicon also encountered difficulties in ramping up production at its Moses Lake facility in 2025. At the wafer stage, Hanwha Q Cells and Corning together account for approximately 5.3 GW of capacity, but operations are still in the process of ramping toward full utilization.

The cell segment began to show more visible progress in 2025, with multiple players placing orders for cell manufacturing equipment. Even so, expansion has remained exceedingly slow. Based on InfoLink’s observations, the timeline from initial equipment inquiries to meaningful commercial production typically spans one and a half to two years, or longer. As a result, nearly 40 GW of planned cell capacity remains far behind schedule in terms of actual mass production.

Incentives and constraints

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), as amended under the current policy framework including the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA), provides Section 45X tax credits for domestic manufacturing, as well as production tax credits (PTC) and investment tax credits (ITC) for clean energy generation projects. Power generation projects that meet the required thresholds for US-manufactured content are eligible for an additional domestic content bonus.

Together, these incentives have supported the development of domestic manufacturing clusters. In practice, capacity expansion continues to face multiple structural constraints. Capital pressures, lengthy land acquisition and environmental permitting processes, coordination with local governments and communities, and limited availability of upstream raw materials have all materially extended project lead times, significantly prolonging both the pre-development and construction phases.

The domestic supply chain for US solar has entered a contradictory phase shaped by the interaction of strong policy incentives and persistent execution constraints. Measures such as the UFLPA, Section 232, Foreign Entity of Concern (FEOC), and tariff policies continue to tighten conditions for imported products while strengthening the rationale for domestic manufacturing.

This latest round of supply-chain screening is reshaping the competitive rules of the US market and, in turn, providing global suppliers with a new benchmark for strategic assessment. Competition will no longer hinge solely on price or nameplate capacity, but increasingly on compliance capability, supply stability, and coordination across upstream and downstream segments.

Companies that can sustain reliable delivery under heightened compliance requirements and elevated uncertainty are better positioned to secure durable competitive advantages as this restructuring unfolds.  Alan Tu

Alan Tu

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.