The United States has set a goal of achieving 100% clean energy by 2035. To do so, a vast amount of land needs to be used for solar energy production. The US National Renewable Energy Lab estimates that if the United States were to meet all of its electricity needs with solar alone, around 10 million acres, or 0.4% of the area of the country, would be needed.

Solar siting can run into local opposition, so public perceptions need to be addressed. That was the subject of “Perceptions of Large-Scale Solar Project Neighbors: Results from a National Survey,” a report conducted by the Energy Markets and Policy (EMP) department at the Berkeley National Laboratory, in collaboration with the University of Michigan and Michigan State University.

The impetus for the study is the tremendous buildout of large-scale solar (LSS) plants (greater than 1 MW) across the United States. According to the US Solar Photovoltaic Database, as of November 2023 there were 3,676 solar projects with capacities of more than 1 MW, for a total generation capacity of 54.9 GW. As of 2022, there were more than 10 million US homes within 4.8 km of LSS plants.

Understanding the perceptions and attitudes of people who live near these installations can help with future deployment, according to Joseph Rand, lead author of the study and an energy policy researcher in the EMP department at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

As no study had previously been done asking LSS site neighbors for input, the Berkeley group teamed up with the University of Michigan and Michigan State researchers to conduct a survey of residents who live within three miles of 380 unique LSS projects ranging in size from 1 MW to 252 MW in 39 states.

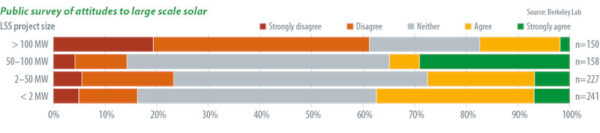

Rand noted that it is early in the analysis of survey results but the key takeaways at this point are that residents had more negative reactions to installations greater than 100 MW in scale. He said the planning process also plays an important role in perception, because if residents “thought the planning process went well, they were more positive overall.”

Part of the planning process is communication about a project. Rand said the biggest surprise in the survey results was that less than one-fifth of respondents actually knew about projects before construction.

A team from the University of Michigan sent out the questionnaire along with a map showing solar power plants in close proximity to survey recipients.

The survey asked several questions aimed at determining how LSS development impacted local tax revenue, supported local workers, or contributed to the local economy overall. On employment, only 18% of respondents thought an LSS project impacted local job opportunities, with 13% of respondents saying it increased employment opportunities and 5% that it decreased them. Almost half the respondents said there would be “no effect” on employment opportunities. Most respondents did not notice any short- or long-term economic impact, although the researchers found that these perceptions were tied to attitudes about projects overall. Likewise, most respondents did not believe that projects affected local inequities.

Researchers were interested in how LSS site neighbors can play a larger role in local development and the responses showed developers can do a better job of informing the public about plans so they can play a role in LSS projects. Questions asked whether respondents were aware of projects, whether developers offered opportunities for neighbors to participate in public meetings during the planning process, and to what extent they had participated.

While respondents did not prefer increased state-level decision-making in future LSS siting decisions, they did want more opportunities to participate in decision-making and liked the idea of having third-party advocates inform neighbors of the planning process and to intervene on their behalf.

In asking how LSS site developers might locate projects that were considerate of local land-use plans, as well as community needs and values, 42% of respondents said they would support additional LSS sites in their community – compared to 18% that would oppose it – but they preferred that projects be sited on disturbed locations such as landfills and former industrial sites, rather than in forests or on productive farmland.

Savvy developers and local officials can gain much from the in-depth report, Rand said. While attitudes in general were found to be more positive than negative, the survey found a significant amount of negativity around very large projects. This is a signal that, if building very large solar sites, “developers really want to listen to the public and do a thorough planning process so people are aware of the project,” Rand said. “If I were a developer, to help the public understand a project, it’s important that that information is provided from trusted sources.” Such sources are not energy developers or state policymakers, but university faculty and staff, or non-profit organizations.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.